A YEAR or so ago, Manolito Madrasto, the executive director of the Philippine Contractors’ Association (PCA), spent an entire day counting vehicles passing through the Olongapo-Gapan road. “It was crazy,” he says. “I just sat there alone in a McDonald’s restaurant while trying to count the vehicles on the road.”

According to Madrasto, the government had agreed to the PCA’s request for the second phase of the Subic-Clark-Tarlac Expressway, which would extend the new toll road to San Fernando in La Union province, to be implemented as a build-operate-transfer (BOT) project with government subsidy. The first phase, in contrast, was funded by Japanese Official Development Aid (ODA).

Madrasto was trying to verify a Japanese consultant’s recommendation for a four-lane highway based on the projected traffic of 25,000 vehicles per day. Local contractors thought the forecasts were way too optimistic. “Where will the 25,000 cars come from?” wondered Madrasto.

Though his “study” was hardly scientific, his skepticism was eventually borne out. When the Department of Public Works and Highways tendered the project last November, it specified that only two lanes be built initially. Two more lanes could be constructed later should traffic volume reach 25,000 passenger-car units per day.

Madrasto suspects the first phase of the Subic-Clark-Tarlac Expressway, which was built with a $355-million loan from the Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC), was likely “over designed” because of awfully high traffic projections.

He says the Bases Conversion and Development Authority (BCDA) is having a hard time attracting good toll management offers from private firms, which doubt BCDA’s traffic forecasts.

After two failed biddings, the BCDA negotiated a deal with a group led by the Lopez family’s First Philippine Holdings Corp. late last year.

But the agreement was only for six months, renewable for another six months, instead of 10 years. In an implicit admission of the dispute with bidders over traffic projections, BCDA chairman Narciso Abaya told journalists the government opted for the interim arrangement “to observe and get accurate traffic volume.”

For Madrasto, the overly optimistic traffic estimates for the Subic-Clark-Tarlac Expressway highlight the government’s tendency to accept uncritically the forecasts of foreign consultants. Or, as Madrasto put it more colorfully, “hook, line and sinker.” He grouses, “There’s no more counter-checking.”

Rene Santiago, a transportation planning consultant and former president of the Transportation Science Society of the Philippines, is more biting in his criticism. “The Japanese consultants tend to bloat and justify projects so they qualify for funding from JBIC,” he says. “Once it gets funded by JBIC, a lot of Japanese construction companies are happy. It’s all part of the usual cozy relationships of Japan Inc.”

Santiago, who has advised transport planners in the Philippines and Asia, says the traffic forecasts for the Subic-Clark-Tarlac Expressway were based on doubtful methods and assumptions.

The Japanese consultants who prepared the feasibility study for Subic-Clark-Tarlac Expressway projected that traffic volume, as measured by passenger car units (PCU), will grow between 2005 and 2015 by 12.5 percent a year for the Subic-Clark section and nine percent a year for the Clark-Tarlac segment.

These growth rates are about twice the historical annual growth in traffic from 1996 to 2002 along existing roads, Olongapo-Gapan road and McArthur Highway, that run parallel to segments of the new expressway.

Santiago says he has not seen anything in the feasibility study that justifies the assumption that traffic growth rates will double. “Traffic usually grows by three to five percent a year as it merely follows the growth in vehicle volume,” he says. “It may grow faster if there is a major property development but these developments take 15-20 years to pan out.”

Santiago cites the example of Makati, which took almost two decades to develop into a central business district. “Besides,” he says, “Clark is not a central business district. We’re talking of an industrial zone here so you can’t assume a lot of passenger-related traffic.”

Indeed, the BCDA’s updated implementation program for the expressway as of August 2004 indicated that the traffic forecasts were built not just on growth trends, but also on what the agency’s Japanese consultants called “traffic from large-scale developments,” presumably arising from growth in investments in the special economic zones of Subic, Clark, and Hacienda Luisita.

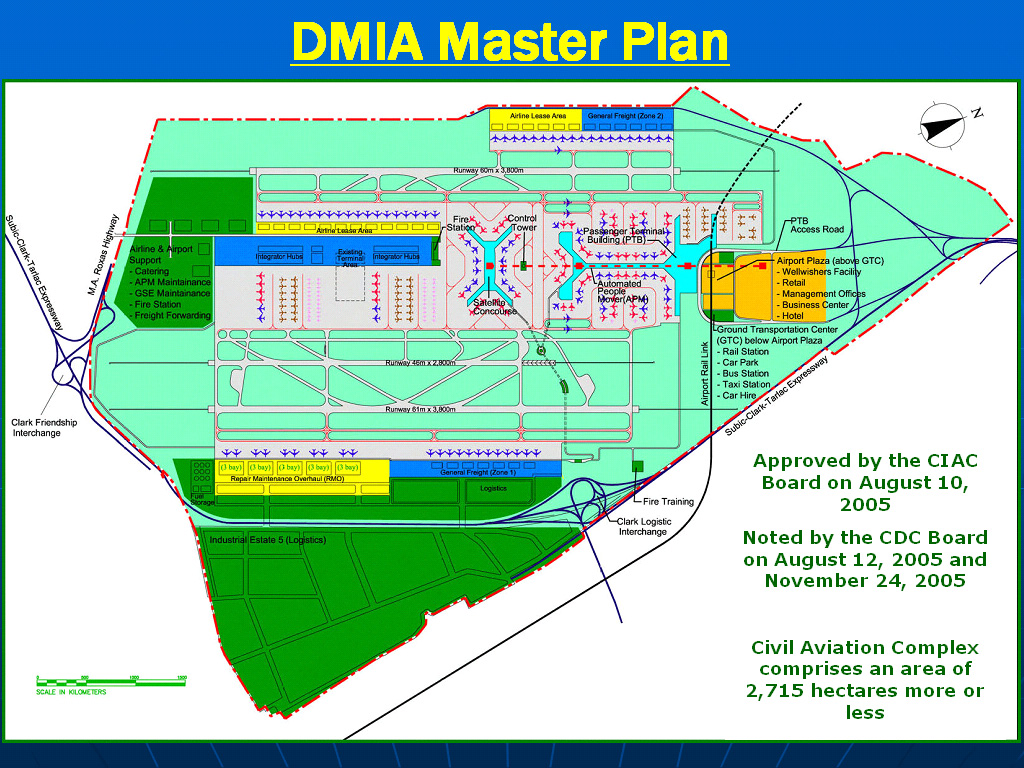

The consultants referred to government plans to increase Clark International Airport’s capacity of 300,000 passengers and 50,000 tons of cargo per year to 40 million passengers and 1.2 million tons of cargo per year.

Plans to boost the Subic Port’s capacity from 25,000 TEUS (twenty-foot equivalent unit, the volume of a cargo container) to 100,000 TEUs were also mentioned.

But Santiago says the consultants did not spell out how such targets would translate to higher vehicle traffic, and when. “Even if the projections come true, bulk of the cargo could be destined for enterprises within the zones,” he says. “That won’t have much impact on traffic to and from the economic zones.”

In another chapter of the report, the Japanese consultants wrote: “The development of the Clark-Subic Expressway and the North Luzon Expressway will enable the converted US military bases to be attractive investment locations for industries with global markets relocating from Taiwan in view of the planned take-over of Taiwan by Mainland China in 2007.”

That may well suggest that BCDA’s Japanese consultants are not just well-versed in toll road planning; they are also geopolitical experts who know for sure not only that China will take over Taiwan, but when it will do so.

No comments:

Post a Comment